Vermont is celebrating its 40th anniversary as a captive domicile this year. The Risk Retention Reporter spoke with captive managers and regulators to trace the history of Vermont as a captive domicile, from the years leading up to the passage of the Special Insurer Act of 1981 to the emergence of risk retention groups in 1987 through to the work being done by the current regulatory team to make sure that Vermont continues to be the “Gold Standard.”

Passing the Law

By the late 1970s, captives were a well-known option for risk financing in the U.S. business community. According to Lincoln “Linc” Miller, founder at Vermont Insurance Management (later USA Risk Group to “be more inclusive”), there were some tax constraints associated with offshore captives that would not be present for an onshore domicile, but no such domicile existed at the time. Interest in establishing an onshore captive domicile was growing at RIMS. “

The fundamental reason was that US companies saw no reason they shouldn’t be able to do [captives] in the United States. Some stockholders did not like the idea that they were in a mysterious offshore domicile and they wanted an alternative,” said Miller.

At the time Miller was working on a project to establish an insurance exchange when RIMS approached him with the idea of establishing Vermont as the first domestic captive domicile, stating “that we don’t need another insurance exchange.”

Miller approached Vermont Chief Economic Development Leader Elbert “Al” Moulton, who had the ear of then Governor Richard Snelling and Vermont Commissioner of Banking and Insurance George Chaffee. Together they worked to begin establishing support for what would become the Special Insurer Act of 1981.

Miller worked with his wife Peg Miller to write a pamphlet educating Vermont legislators on captives. Both Moulton and Miller worked on putting together meetings with legislators on the bill. Moulton also had a rule in place where risk managers were banned from testifying on the proposed captive law.

Miller related an incident at one of the meetings at the Commerce Committee. In the middle of a discussion on workers comp captives an individual identified himself as a former risk manager and offered to answer a question posed by the committee.

“Afterwards, I grabbed the guy and told him he wasn’t supposed to be testifying. He said he wasn’t a risk manager anymore and had an association in Vermont, but Moulton was really upset,” said Miller. “I think Vermonters wanted to scrutinize us, to make sure we weren’t evil people.”

Moulton wanted to keep the focus on the benefits for the businesses that would forming captives and for the State of Vermont itself. The strategy worked.

According to Miller, Governor Snelling was the most important figure in getting the law passed stating that if he had said no “we’d be talking about South Dakota.” Other key players included Chaffee and Edward “Ed’ Meehan, who later became Vermont’s first director of captive insurance.

“Chaffee was more of a political regulator at first—very intelligent, affable, and charming,” said Miller. “Ed was the assistant to George and had more knowledge as a regulator, knew the ins and outs.”

“The law itself was not something that was wild. It had a lot of controls and focused those controls on the regulators. The governor was strong behind it. And the politics were strong behind it.”

According to Miller, Chaffee hedged his bets for a bit, but later became a good supporter of the law. Chaffee later left regulation and became a partner of Miller’s at Vermont Insurance Management. Meehan, who had been hired from the Massachusetts Department of Insurance, was a tougher sell.

At the time domestic regulators did not have real experience with captives other than interacting with mechanisms they didn’t like. Miller stated that, during his time in Massachusetts, Meehan saw a company go bankrupt due to the failure of its captive insurer.

“Ed was sour grapes at the beginning. He started from the position that captives were what made good companies go broke,” said Miller.

Meehan, who later became a critical figure in Vermont’s success as captive domicile, saw his position on captives soften due to the strength of the presentations and the law itself, as did many others with concerns about the law.

“The law itself was not something that was wild. It had a lot of controls and focused those controls on the regulators. The governor was strong behind it. And the politics were strong behind it,” said Miller.

The Special Insurer Act of 1981 ended up passing unanimously in the Vermont House and saw a single nay vote in the Vermont Senate.

“From the point of view of Vermont, there were nothing but positives. It was a clean business. Vermont wants clean business, always did. The state was in a position where only certain things can have economic strengths in a remote location like that. When the Bill was passed, there was a comment from someone at Johnson & Higgins (now a part of Marsh) that you ‘take two planes and a canoe to get to the domicile,’” said Miller.

Vermont, like many of the earliest captive domiciles, was largely a tourism economy.

“We started with George Chaffee and Governor Snelling looking at the captive law and thinking ‘what have we got to lose?” said Provost. “This will bring in some tax revenue, it’ll bring in some white-collar jobs, and it’ll bring in some tourist dollars. The first captive domiciles were all tourist economies. That was the driver for Bermuda, Vermont, even Hawaii—we want to bring in more tourism revenue—but it turned into so much more.”

Many of the individuals who worked to make Vermont the first domestic captive domicile have since passed on. George Chaffee, who later became the founding director of the Vermont Captive Insurance Association and was fixture at VCIA Conferences as recently as the late 2010s, passed away in February of 2021.

Governor Snelling served from 1977 to 1985. In 1986, he ran for U.S. Senate but lost to Senator Patrick Leahy. Snelling was again elected as Vermont’s Governor in 1990 but passed away less than a year into his term.

Moulton, who was born in Maine, worked as economic development leader under four different governors. Initially appointed by Governor Philip H. Hoff (1963-1969)—at the time Vermont’s first Democratic Governor since 1853— Moulton himself served as the Chairman of the Vermont Republican Party in the late 1960s. Moulton played a part in another defining aspect of Vermont: the banning of billboards in the state. Moulton passed away in 2011.

“Al Moulton was accepted as a true Vermonter: He was called Mr. Vermont. The guy was really good at his job. Everyone trusted him. He was originally appointed by Democratic governors. We didn’t have that kind of partisanship that exists today. Everybody was able do the best thing for Vermont and it worked out great for the state. It’s amazing. I really wonder what the total impact was,” said Miller.

Laying a Foundation

The bill was presented at the 1981 RIMS Conference, and though there was some initial skepticism, there were enough risk managers at the time who wanted to utilize the captive vehicle domestically that the first Vermont captive—First Charter Insurance Company—was formed by BF Goodrich in the fall of 1981.

“The fact was a significant number of risk managers wanted this vehicle, and they were utilizing it without a crisis for the fundamental financial reasons that we do today,” said Miller. “The fortuitous thing was that from 81 to 85, before we had any real volume coming in, we had very sophisticated risk managers working in the state.”

A committee was set up to educate the Vermont regulatory body. The committee included captive managers, actuaries, and other captive professionals. In the early years Meehan would review each captive application with the committee to better understand the captive insurance industry. “Meehan became very well trained over a period of years,” said Miller.

The advisory committee was dissolved once Meehan felt the Vermont captive division had sufficient captive insurance experience. Miller also noted that Meehan was a “naturally conservative regulator” and was deliberative in the captives that he licensed in the state. Vermont was “fortunate not to have a lot of wild players,” said Miller.

Risk Partners Vice President, and Former USA Risk Group President, Gary Osborne said that another important component of Vermont’s foundation as a captive domicile were the early captive managers— Scott Frazier, Arthur Koritzinsky, Ann Wick, and Kathryn Westover—that drove Vermont in the early years. “I felt like I was along for the ride, but things really took off due to those early pioneers,” said Osborne.

Transitions

In 1990, Len Crouse—the Chief Examiner of the Property and Casualty Division in Massachusetts—was brought on by Ed Meehan to take his place as the Director of Captive Insurance for the State of Vermont. Meehan had known Crouse from his time in the Massachusetts Department of Insurance. Crouse would go on to lead the Vermont Captive Division for 18 years.

Crouse carried on the conservative regulation principles that Meehan established. According to Osborne, Crouse had a rule: “if it has wheels, I don’t want it.”

And for a while there were no trucking or commercial auto risk retention groups in the State of Vermont.

“Len would tell you if a captive wasn’t going to work in Vermont. A lot of states could still learn from that: don’t be afraid to say no,” said Osborne.

That conservative approach can also be seen in Vermont’s avoidance of the troubles surrounding 831(b)s. While Vermont allows its smaller captive insurers to claim the designation, the state has not actively pursued 831(b)s.

“Len was stern in his approach yet appreciated the value of being flexible when circumstances allowed for it. Vermont’s regulatory mission that exists today was developed and influenced by the hard work and dedication of Ed and Len,” said Vermont Director of Captive Insurance Sandy Bigglestone. “We work with the same values and approach to regulation that has contributed to Vermont’s success over the last 40 years.”

Miller believes that the regulatory foundation established in those years following the passage of the captive law are a critical component of Vermont’s long-term success.

“Vermont has been superior in many ways due the independence and strength of regulatory powers that are assigned to the captive division. That strength was built up by the training they received from the right industry people. Vermont built up a knowledge base and then focused on what they wanted,” said Miller.

Miller stepped away from USA Risk Group in the 1990s after being diagnosed with stage four cancer. “Gary and Andrew Sergeant stepped up and became phenomenal for the company, the growth since those days can be attributed to them,” said Miller.

RRGs Enter the Scene

In 1985 the insurance industry entered an unprecedented liability crisis, not only increasing interest in captives, but also spurring action in Washington, D.C. Work was being done on the development of a new insurance vehicle.

Around that time Jon Harkavy joined Linc Miller’s team at Vermont Insurance Management. Harkavy, Miller, and Al Moulton traveled to Washington to meet with Vermont Senators Patrick Leahy and Robert Stafford to get interests from Vermont’s point of view into the bill.

“At the time Vermont had mechanism in place for group captives, but it didn’t foresee anything like risk retention groups,” said Miller. “It was a tremendous change to the whole administration of insurance law. Thank god they did it.”

The Liability Risk Retention Act was signed into law in 1986 allowing for the formation of risk retention groups and purchasing groups. Risk retention groups were particularly radical in their construction—allowing for insureds with a homogeneous risk to band together and form their own insurance company. Furthermore, RRGs needed to domicile in just one state to write business in all other states. A striking change to the traditional model of state-based regulation of insurance.

“At the time Vermont had mechanism in place for group captives, but it didn’t foresee anything like risk retention groups,” said Miller. “It was a tremendous change to the whole administration of insurance law. Thank god they did it.”

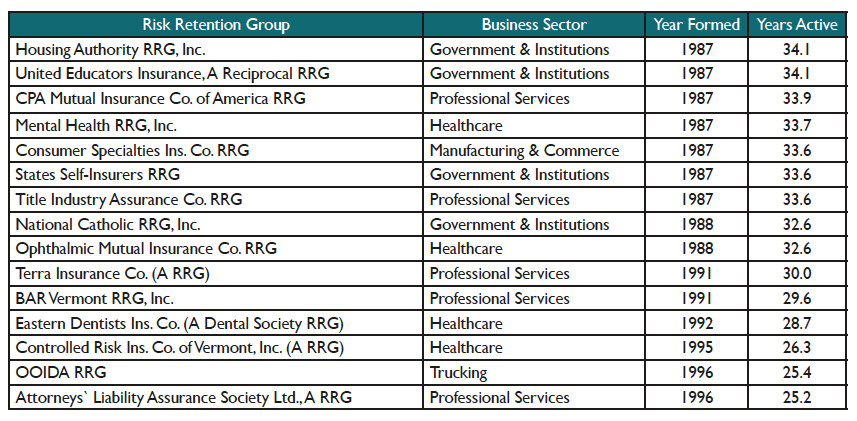

Risk retention groups quickly found a welcome home in Vermont. There are 31 risk retention groups that of been active for 25 or more years—fifteen of those groups are domiciled in Vermont. Vermont was also one of the only domiciles to continue to form risk retention groups through 1990s, after the initial excitement of the LRRA passed. Vermont is now home 36% of all risk retention groups. Much of that growth occurred under Len’s guidance.

“Len was a champion regulator for risk retention groups and often advocated for the business of risk retention groups for Vermont because he understood the value risk retention groups hold for their members,” said Bigglestone.

Even so, the risk retention group vehicle has its challenges: “I think RRGs are spectacular, but you can get in a lot of trouble with them,” said Miller.

Miller related interactions he had with Louisiana State Senator Michael O’Keefe. Miller said he stopped working with O’Keefe at the last minute. “There’s a lot of players that you’ve got to be very careful of,” said Miller.

O’Keefe went on to form Physicians` National RRG, Inc., the first and only risk retention group domiciled in Louisiana. Physicians’ National was declared insolvent in 1991 and in 1999 O’Keefe was sentenced to 20 years in prison for skimming over $4 million from the risk retention group.

Miller also got into what can only be called positive trouble with RRGs in Vermont. According to Miller, in the 1990s there were a lot of associations with real needs, but no money. One such association was OOIDA—an international trade association that represents independent owner operators and professional drivers.

Miller noted that he got in hot water with Vermont regulators because OOIDA RRG was initially set-up as 100% reinsured program. Although the program was safe, it was considered by regulators as a direct writer from offshore.

“The purpose of the structure was to take an association of members who weren’t capital intense, but had a severe exposure, and to give them an opportunity to build up,” said Miller. “When members paid a premium, they also had to pay a capital contribution, so that over a period of time they built up a capital fund.”

OOIDA RRG was set-up with an assumption agreement, meaning that when capital at the RRG reached a certain level the RRG would start retaining premium. The structure was a successful one. OOIDA RRG first wrote premium in 1995 and by 1998 had begun to retain premium. Now OOIDA RRG is second longest operational risk retention group in the Transportation sector and is considered a model for how risk retention groups can successfully insure truckers.

The legacy of Vermont’s risk retention group activity in the years following the passage of the LRRA is in groups like OOIDA RRG, or Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Co. (A Risk Retention Group), which continue to serve their members 20 or 30+ years after they were formed.

A New Generation in the Boom Years

Vermont saw a surge of activity in the 2000s, forming a record 70 new captives in 2003, including 11 risk retention groups. At the time, the next generation of leaders in the Vermont Captive Division was moving up the ranks, including Dave Provost.

Vermont RRGs Operational for 25+ Years

“I started my regulatory career as an examiner. I wanted to do something different—to see what’s like on the regulation side. Frankly, the best job I ever had was being a captive examiner,” said Provost, who was a captive manager before joining the Vermont DFR. “When you work for a manager, you see your six to ten clients and you see how they work, and how the management firm works. If you’re in regulation, you see everything, you’re looking at all 600 companies, and how each one is managed differently.”

Provost remembers an old employee list that the Vermont DFR had. Provost started at the bottom, but as the number of captives surged, he quickly found himself in the middle of the employee list. Provost describes those years as a “steady exam process and a stream of new hires.”

The future leaders at the Vermont DFR working their way through the ranks in those years include Sandy Bigglestone and Vermont Division of Captive Insurance Chief Examiner Dan Petterson.

“We’ve always said that the best RRGs are those that are member driven. That is the key. If the members need this, and the members support it, and the members run it, then it is likely to be a successful RRG.”

Len Crouse retired from his position at Vermont DFR in 2008 with Dave Provost being appointed as the new Deputy Commissioner that year. Bigglestone and Petterson stepped into their new roles of Director of Captive Insurance and Chief Examiner, respectively, in 2010.

“Our biggest accomplishment is maintaining our standards,” said Provost of his team’s time at the helm of the Vermont Captive Division. “We’ve gone through a lot of changes. Dan Petterson had to manage the transition from paper to electronic examinations. We were also going through some big changes at the NAIC, in terms of the rules and requirements for risk retention groups. We were trying to take the best of what traditional regulation has to offer and apply that proportionally to captives. Through all that Sandy was working to make sure our laws and procedures were up to date with NAIC processes and that processes for licensing companies were working correctly. It’s not any one particular accomplishment, but we did that all while licensing 400 new captives.”

Vermont in 2021

Vermont is now the third largest captive domicile in the world—behind only Bermuda and the Cayman Islands— and in 2021 licensed its 1200th captive insurance company. Vermont has received numerous domicile of the year awards—maintaining its status as the gold standard.

“Since the passing of the Special Insurer act in 1981, Vermont’s regulators have followed a mission to attract quality programs, business that promotes the reputation of the industry and safeguards the solvency of companies that choose to do business in Vermont,” said Bigglestone. “Our approach is not all about the numbers, growing the number of licensed entities here, but in having a quality set of rules and best practices, and implementing them well. The focus is on maintaining a trusted reputation, continuously learning, and maintaining infrastructure support has naturally grown the business over the last 40 years.”

Even with its success, Vermont has had its challenges, including a recent flare-up in risk retention group insolvencies. The three insolvencies over the last two years included two risk retention groups that had redomiciled from other states.

Taking those recent insolvencies into account, Vermont still maintains the second lowest insolvency rate among established domiciles—disregarding domiciles that have only formed a handful of RRGs—behind only Hawaii. Even with the recent hiccup, risk retention groups remain an important part of the captive vision for Vermont.

“We like working with risk retention groups. The RRG tool is a really valuable tool for a lot of companies, but it generally indicates that there is an issue with the marketplace,” said Provost. “We’ve always said that the best RRGs are those that are member driven. That is the key. If the members need this, and the members support it, and the members run it, then it is likely to be a successful RRG.”

Now the Vermont Captive industry is welcoming its third generation. Provost noted he used to work with Captive Insurance Economic Development Director Brittany Nevins’ mother at Johnson & Higgins in the 1990s and that his son is now working in the Vermont Captive Industry as well.

“The captive industry has developed into a vital part of Vermont’s economy,” said Provost. “So, we’re going to stay on top of it. We’re going to make sure we have a captive bill every year. We’re not just going to maintain our accredited status with the NAIC—we’re going to pass with flying colors. We’ll learn from every insolvency and every troubled company, and from every successful captive. We’ll keep learning and moving forward. There are a lot of people in Vermont who rely on the captive industry.”

Article courtesy of The Risk Retention Reporter.